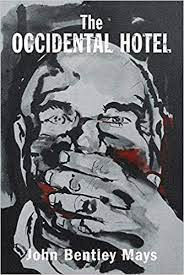

The Occidental Hotel by John Bentley Mays

- May 2, 2021

- 3 min read

Updated: May 2, 2021

Reviewed by Ian Thomas Shaw

An eccentric novel, The Occidental Hotel, will not be of interest to many CanLit readers. Mays does not champion a millennial cause or anguish over childhood trauma. There is no self-flagellation or grief. No character is Canadian nor does any part of the setting take place in Canada. A superficial reading of the novel might even lead some to see it as steeped in bigotry and misogyny. But that is assuredly not the intention of the author, whose long career as the Globe and Mail’s art critic establishes him as a progressive liberal.

What the novel does is offer interesting perspectives on two difficult topics: racial nationalism in the American deep south and life for ordinary citizens in pre-war Nazi Germany. Mays, who died in 2016, attempts to capture the social practice and thinking prevalent in the Louisana of his youth and then in parallel explain the life of German artist Joseph Beuys, an object of Mays’ fascination for decades. The novel, finished only two weeks before Mays' death, was published with three explanatory essays by prominent members of the Canadian literary community. To experience fully this unique work of fiction, it is useful to read these essays beforehand.

The book’s narrator hides from the police in a largely deserted resort hotel somewhere in Louisana. The crime he has committed remains shrouded in mystery for most of the narrative. At the hotel, he begins to write a biography of a radical German artist named Jupp. This is obviously Joseph Beuys in real life as photographs of Beuys’ work are interspersed throughout the book along with lengthy commentaries. The biography has an audience of one, Alexander, a boy abandoned at the hotel by the “Travelling Folks,” possibly a reference to Roma. The child prods the narrator to go into ever greater detail of the German artist’s life, in particular his possible sexual orientation. Allusions to Jupp’s repressed homosexuality keep cropping up in the novel, but clarity on this point is never truly established. For a novel written in 2016, it seems rather dated to present sexual orientation in such a circumspect way. Indeed, Mays was very much a man of a different era. Although in his earlier life, he was in the cultural vanguard, his only stab at novel-writing toward the end of his life suffers from a subtly anachronistic tone.

The novel alternates between Jupp’s story and the narrator’s childhood in the American South. The narrator comes from a position of white privilege in a society, whose values are slowly eroding. The vestiges of the Old South give the writing a Gothic feel, foreboding the descent of the narrator into racist reactionism and the eventual commission of a horrendous hate crime.

What Mays does well in the novel is to write impeccable prose and create suspense. There is a lot of “where is he going with this” throughout the book or perhaps better put “is he really going in that direction.” To a certain extent, he does stir up some empathy for his confused anti-hero narrator. Capturing the Zeitgeist of the experimental artists of the 1970s and 80s is another notable feature of Mays’ writing. The author was, after all, Canada’s leading art critic. While only a handful of readers will cotton on to the deeper significance of the seemingly bizarre performance art of the character Jupp, the narrative may perk the curiosity of many readers to learn more of the artistic movement that fascinated Mays so much. These positive points only partially redeem the novel, but if you are saturated with the usual CanLit grist and wish to challenge yourself with something oddly aesthetic and mildly disturbing, this novel might be for you.

The Occidental Hotel is published by Guernica Editions.

Comments